House of the Dragon vs. Modern Audiences

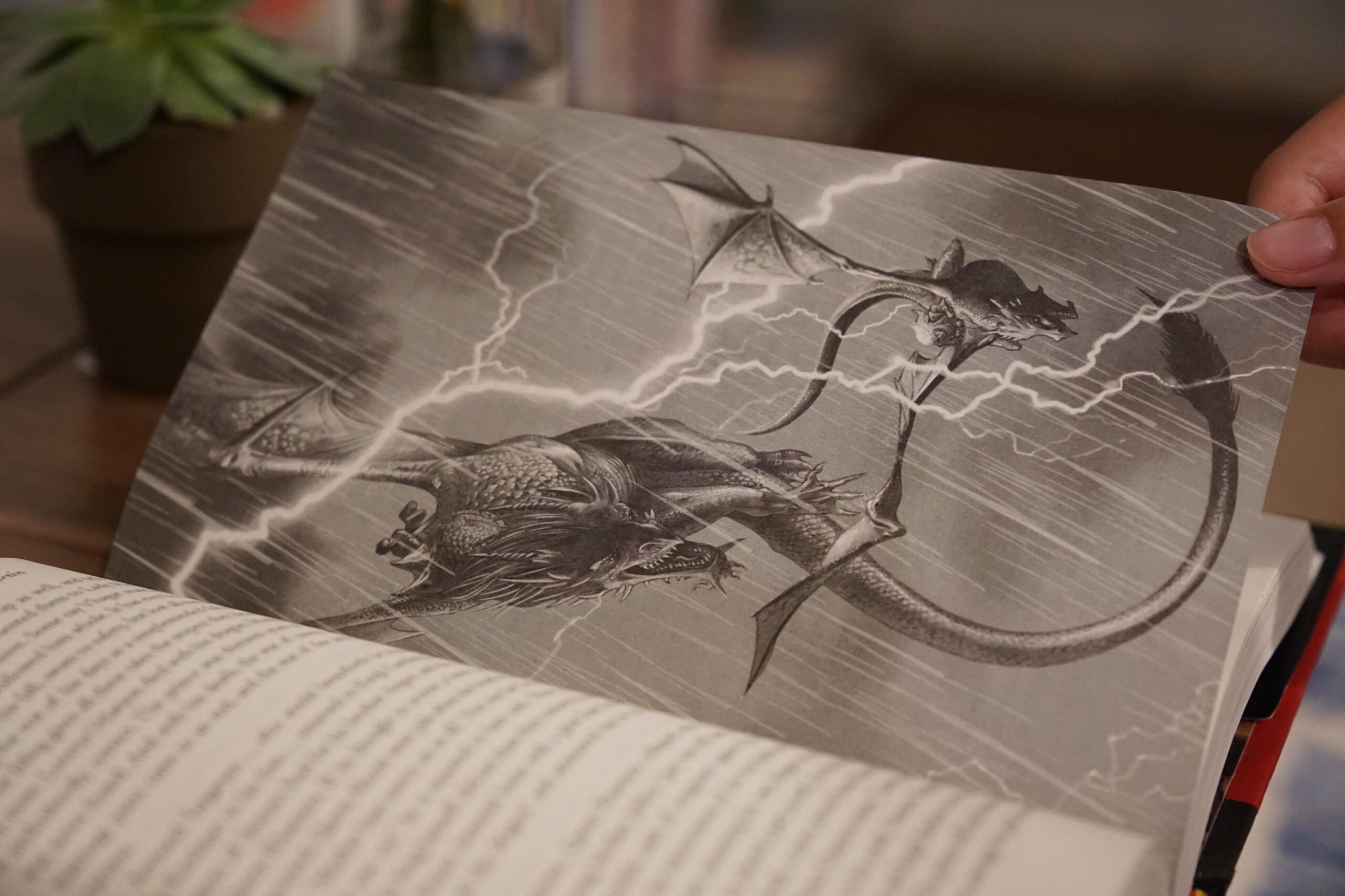

Not too long ago, I binge-watched HBO’s House of the Dragon (henceforth HOTD), a prequel spinoff of its acclaimed television series, Game of Thrones (henceforth GOT), itself an interpretation of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (henceforth ASOIAF) book series. HOTD follows a specific epoch predating the events of GOT by almost 200 years — that is, it is based largely off the events of a civil war referred to as the Dance of Dragons — the details of which are captured in the fictional history also authored by Martin, Fire and Blood. Fire and Blood is presented as a neutral treatise, a fictional piece of nonfiction, that is canonically intended to depict the rival Black and Green factions as equally likable — or, such as it were, as equally unlikable.

As much as I thoroughly enjoyed HOTD, I personally find that the show did not retain the measured impartiality of the source material; rather, I can’t help but feel that the series strongly favors the Black faction, so much so that its figurehead, Rhaenyra, is effectively the show’s protagonist. Though I find this characterization a bit disappointing given the uniquely neutral framing of Fire and Blood, I posit that there are several reasons for it, namely:

- The structure and purpose of storytelling, specifically its need for a protagonist;

- The tension between a modern audience and propagation of a dated form of primogeniture; and

- The asymmetry between the leaders of the Black and Green factions.

I will explore each in turn. As this post is largely a reflection of my thoughts on the series, please note that it will contain unmarked spoilers.

The Art of Storytelling

Fire and Blood, the book off of which HOTD is based, is a piece of fiction that reads as if it were a piece of nonfiction. It is framed as a supposedly neutral historical account of the history of the Targaryen dynasty, cobbled together by numerous primary and secondary sources of varying degrees of reliability (as, indeed, are many of our own world’s historical accounts). Because Fire and Blood isn’t presented as a piece of prose, it has the ability to be uniquely neutral in a way that novels — which by virtue of what they are, often require some sort of protagonist, if only for the purpose of narrative framing — simply cannot.

HOTD, however, is a piece of fiction that presents itself as a story to its audience; it isn’t packaged, say, as a documentary, the rough television equivalent of a work of nonfiction. Because it is presented as a story, HOTD is bound by the norms and customs that dictate what generally makes good storytelling. Chief among these is the need for a protagonist, or a character through whom the audience experiences the story, and in whom they are meant to become invested.

The Need for a (Sympathetic) Protagonist

It is difficult to tell any sort of story without a main character. That isn’t to say that it’s impossible, but I am an avid reader myself, and have yet to encounter a work of fiction completely devoid of characters. Characters, particularly main characters, serve critical roles in any plot — they may function as a narrator, through whom the story is told; they may serve as a figure with whom the audience is meant to empathize; or perhaps they may act as an avatar of sorts, through whom the reader or viewer escapes their own reality and fully immerses themselves into that of the fiction. But I find their most important function to be a combination of the above — namely, the main character serves as an orientation device for readers. To that end, the main character at a minimum acts as a frame of reference for the audience: we are implicitly encouraged to perceive the fictional universe as they do, and it is generally easier to do so if the protagonist is a sympathetic, likable person.

That said, we as the audience are not constrained by the protagonist’s perception, which is to say that we are not compelled to align our viewpoints with those of the protagonist. We are free to disagree with their decisions, thoughts, actions, etc., and indeed, there are such things as unreliable and unlikable narrators (Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn and A Separate Peace by John Knowles, respectively, are good examples of each).

Nonetheless, choosing a protagonist mirrors casting the lead in, say, a stage production; the showrunner will still ideally want to pick someone who is good at what they do, who can perform compellingly and evoke strong feelings (positive or negative) in the audience. While powerful stories with distasteful lead characters do exist, such works generally adopt a somber, taut mood that seems ill-suited for HOTD; and even in such cases, the protagonist is rarely completely devoid of any redeeming qualities whatsoever. It remains ideal, I contend, to pick a protagonist with whom audiences can readily empathize and around whom they can rally; fiction is, after all, generally a form of escapism, and I would imagine that most people would prefer to escape into someone likable, who at least has the potential to arouse their sympathy.

If there is any doubt that HBO chose to embrace Rhaenyra as the series protagonist, look no further than HOTD promotional material, which prominently features Rhaenyra.

Patrilineal Primogeniture vs. Modern Sensibilities

HOTD takes place in what might best be described as medieval times and, as in our own world, that particular era was not especially kind to women or those of less-than-noble birth. Indeed, the civil war that HOTD follows comes about when Rhaenyra, a woman and the leader of the Blacks, is named her father’s heir in contravention of the long-held precedent that the king’s eldest son inherits his titles and position; her reign is thus challenged by her half-brother Aegon, the oldest son of the late king, and those that support patrilineal primogeniture as a continued basis for inheritance, collectively the Greens.

The audience to which HOTD caters, however, mercifully belongs to a much different time period; and accordingly, viewers inevitably bring their modern sensibilities with them when they watch the show. We are fortunate to live in a century wherein it is generally recognized that:

- Sex should not be an impediment to inheritance, status, or position;

- The circumstances of one’s birth should not define their capacity to rise; and

- Society largely benefits when positions of power and influence are assigned based on merit and capability rather than connections, familial or otherwise.

That being said, it is difficult if not impossible for modern audiences to instinctively sympathize with Rhaenyra, whose claim to the throne is being disputed solely on the grounds that she is a woman and thus too feeble to inherit. We as a modern audience immediately recognize the injustice being dealt Rhaenyra, and are all too ready to rally behind her. This already reflexive decision is made even easier by the fact that Rhaenyra is portrayed as a levelheaded, prudent woman, whose great compassion still manages to have certain contemporary heat to it. Even her few flaws are essentially spun as qualities — her reluctance to marry for duty is framed as her being spirited and rebellious; her resentful insecurity about her place in the succession is framed more as a criticism of the patriarchy, and is further worked to humanize Rhaenyra by demonstrating that she is not as confident, borderline cocky, as she sometimes seems.

Meanwhile, Aegon is portrayed as almost comically devoid of any redeeming qualities — he is flagrantly supercilious, lecherous, hedonistic, and cruel; in fact, his debut scene as an adult sees him sexually violating a servant, something difficult if not impossible to come back from in the court of public opinion. As if that isn’t enough, it is later revealed that Aegon enjoys watching children fight to the death, and has fathered numerous bastards, some of whom participate in these death matches. The only moment in which Aegon elicits any sympathy might be when he abruptly asks his mother whether she loves him en route to his coronation, suggesting that he has never received any such affirmation from his parents; and this line was apparently improvised by the actor (Tom Glynn-Carney).

Given that modern audiences are already inclined to side with Rhaenyra, showrunners began the series facing an uphill battle in portraying the Greens as sympathetic. But it almost seems as if they decided not to even try, at least regarding Aegon himself; and given that it is Aegon who is diametrically opposed to Rhaenyra with respect to who should sit the Iron Throne, I find this more than a little frustrating.

An Attempt at Equitableness

Now, it is important to note that believing that the showrunners have chosen to portray Rhaenyra as the series protagonist, and Aegon as the one-dimensional antagonist, is not inconsistent with recognizing that they have also made a great many adaptational changes in favor of the Greens. Indeed, showrunners made substantive changes moving from the source material to the screen that portray the Greens in a much kinder light. Perhaps the most significant changes are as follows:

- The childhood friendship between Alicent and Rhaenyra was fabricated for the purposes of HOTD. Critically, the showrunners’ decision to focus on the relationship between Alicent and Rhaenyra has the effect of elevating Alicent, rather than Aegon, as the emblematic leader of the Green faction.

- Alicent’s motivation to push Aegon onto the throne is rooted in fear, not ambition. While Alicent is still just a young woman herself, her father Otto impresses upon her the idea that if Rhaenyra is allowed to inherit the throne, she will have no choice but to execute Alicent’s children to perfect her claim and silence dissent. When the time ultimately does come, she is again only persuaded to advance Aegon’s claim when she misinterprets Viserys’s last words as a dying wish that Aegon be named his heir instead of Rhaenyra.

- Aegon’s most heinous qualities are toned down or removed entirely, most notably his record of sexually exploiting young children. Granted, in Fire and Blood, the allegations of Aegon’s sexual deviance stem from an unreliable source that is partial to Rhaenyra; but the showrunners’ decision to omit any references to it is arguably one that benefits Aegon’s character — or at least, saves it from crossing the point of no return in the court of public opinion.

- Aemond’s killing Lucerys Valeryon is portrayed as an accident, instead of the intentional act of murder it seems to be in the source material. In Fire and Blood, Aemond deliberately hunts Lucerys down atop his dragon, Vhagar, and derives great pride in his newfound status as a kinslayer. Conversely, in HOTD, Aemond loses control of Vhagar, who kills Lucerys of her own volition; perhaps more importantly, Aemond is visibly horrified upon realizing what he has done.

Of the foregoing creative changes, the showrunners’ decision to dramatically expand upon Alicent’s character is both the most substantive, and the one that most readily lends itself to further discussion.

The Elevation of Alicent

The elevation of Alicent, effectively, to the role of secondary protagonist is a change that I personally like, but it does create a bit of an asymmetry between the faction leaders — Rhaenyra is the leader of the Blacks; while in the source material, Aegon is the leader of the Greens. At the very least, it is clear in Fire and Blood that it is Aegon who is diametrically opposed to Rhaenyra, rather than Alicent.

The showrunners’ decision to center the Green faction around Alicent as its matriarch, rather than around Aegon as its candidate for the throne, was likely calculated to improve the Greens’ image. The Greens, after all, symbolize male primogeniture and by effect male supremacy; while the Blacks symbolize — at least at a very basic level — gender equality. Thus, the creative decision to focus HOTD on Alicent, a woman, instead of Aegon, was probably intended at least in part to make the Green faction a little more sympathetic to modern audiences.

It is tempting, then, to equate Alicent with Rhaenyra, insofar as they both appear to be the leaders of their respective factions; but I personally find that to be a flawed comparison. Because no matter how sympathetic, complex, or compassionate showrunners make Alicent herself out to be, her cause is inextricably tied to that of Aegon, a licentious degenerate who has been given no redeeming qualities with which to win any goodwill from audiences. Alicent herself could be a veritable saint; but so long as she is championing the claim of her morally bankrupt son, it is difficult if not impossible to divorce her from the depravity that he represents. Their causes are linked, such that one cannot support Alicent without also supporting the debauchery and savagery of which Aegon is emblematic.

Accordingly, the showrunners’ best efforts to introduce depth and complexity to Alicent’s character — and thus, to the Green cause — are ultimately ineffectual; and this will hold true as long as they insist on portraying Aegon as being almost comically devoid of any positive attributes whatsoever.

A Product of Its Time?

Given our modern sensibilities, is it even possible to write HOTD such that viewers could sympathize with the Green faction? It is difficult to say. Aegon and the Greens represent the celebration of agnatic primogeniture, itself inextricably linked to the (hopefully outdated) idea of inherent male supremacy; conversely, Rhaenyra and the Blacks represent the celebration of gender equality, and to some extent, meritocracy. In the court of (modern) public opinion, it is hardly an even playing field.

Certainly, the showrunners (and the Greens) had the cards stacked against them in depicting the Green faction so as to elicit viewer goodwill. Indeed, their decision to center the Green faction around Alicent rather than Aegon may have been calculated to do so. But its efficacy is completely undermined by showrunners’ caricaturistic portrayal of Aegon as a self-indulgent, unscrupulous youth — given that it is his claim that Alicent is advancing, however virtuous she herself may be. Still, the legitimacy of Aegon’s claim as compared to Rhaenyra’s would have been a thorny issue, even if Aegon was portrayed as being wise and benevolent (look no further than Viserys’s advancement over that of his cousin Rhaenys). Maybe, then, it was always a foregone conclusion that viewers would overwhelmingly side with the Blacks, as polls have shown them to do.

Whether the Greens can ever win the hearts of modern audiences is a question to which I, certainly, don’t have the answer. Perhaps Season 2 will tell.

The content of this post constitutes an expression purely of my personal opinion and conjecture, and accordingly, is intended only to entertain rather than to inform or instruct. If you see any errors, please *****@*******ol.me”>let me know.

Photography by Ryan Chang

plenka samokleushayasya zashitnaya_iski

September 4, 2025 at 6:40 pmсамоклеющиеся пленки на стекло [url=www.samokleyushchayasya-plenka‑1.ru]самоклеющиеся пленки на стекло[/url] .

dizainerskaya mebel_vsei

September 4, 2025 at 6:41 pmдизайнерская мебель комод [url=http://dizajnerskaya-mebel‑1.ru/]дизайнерская мебель комод[/url] .

binance

September 14, 2025 at 4:20 amCan you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

create binance account

September 15, 2025 at 8:03 amThanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

create binance account

September 15, 2025 at 1:38 pmThanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Регистрация на www.binance.com

September 21, 2025 at 6:13 pmYour point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Zarejestruj sie na Binance

September 22, 2025 at 5:07 amThank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Crea una cuenta gratis

October 5, 2025 at 7:36 pmYour article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

www.binance.com注册

November 13, 2025 at 12:06 amYour point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Binance美国注册

November 15, 2025 at 2:40 amThanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

bono de registro en Binance

November 26, 2025 at 5:01 amYour point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Buôn bán nội tạng trẻ em

December 4, 2025 at 3:19 amMua bán, trao đổi nội tạng trẻ em, đặc biệt trẻ em dưới 13 tuổi. Nhấp vào link hiển thị để được tư vấn và báo giá.

hepatoburn

December 26, 2025 at 11:57 am**hepatoburn**

hepatoburn is a high-quality, plant-forward dietary blend created to nourish liver function, encourage a healthy metabolic rhythm, and support the bodys natural fat-processing pathways.

criac~ao de conta na binance

December 30, 2025 at 12:40 pmYour article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

prostabliss

January 20, 2026 at 11:55 am**prostabliss**

prostabliss is a carefully developed dietary formula aimed at nurturing prostate vitality and improving urinary comfort.

mounjaboost

January 23, 2026 at 11:11 am**mounjaboost**

MounjaBoost next-generation, plant-based supplement created to support metabolic activity, encourage natural fat utilization, and elevate daily energywithout extreme dieting or exhausting workout routines.

QQ88 COM

January 31, 2026 at 2:58 amQQ88 mang đến nền tảng giải trí online hiện đại, tối ưu hiệu suất truy cập, thao tác đơn giản, vận hành ổn định và đảm bảo sự thuận tiện cho người dùng trên nhiều thiết bị.

QQ88

January 31, 2026 at 2:26 pmQQ88 là cổng truy cập giải trí trực tuyến ổn định, hỗ trợ người dùng tiếp cận hệ sinh thái game đa dạng với giao diện mượt, tốc độ nhanh và trải nghiệm liền mạch.

地狱乐第二季爱一帆

February 1, 2026 at 11:16 pm官方授权的一帆视频海外华人首选,第一时间提供最新华语剧集、美剧、日剧等高清在线观看。

QQ88

February 5, 2026 at 2:23 pmQQ88 cung cấp nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến ổn định, tập trung vào tốc độ truy cập, giao diện thân thiện và trải nghiệm liền mạch.

accounts.binance.com Inscreva-se

February 5, 2026 at 4:44 pmThank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

newonlinecasinos

February 6, 2026 at 9:28 amBest Australian Casino Real Money Real Players Cashing Out Massive