A (More) Realistic Approach to Quantifying Love

You may recall that I am of the strong opinion that love — really, any sort of emotion along the spectrum of human feeling — cannot be reliably quantified. At the very least, I don’t think it can be numerically quantified in any persuasive way à la the economic concept of cardinal utility. But the fact remains that we as humans do exhibit preferences; which is to say, that we like or love some things more or less than others.

It is clear, then, that we can and do implicitly measure our feelings. That leaves me with a number of questions — namely, how do we measure our feelings? Are we conscious that we are doing so? Does it matter whether we are, and what are the implications either way? Maybe there are answers to these inquiries, and maybe (indeed, likelier) not. Whatever the case, I think that they can be boiled down to a simpler question, and one that may be fun to explore:

Is there a (more) realistic approach to quantifying love?

The Economics of Feeling

Acknowledging that we as humans exhibit preferences suggests that our feelings are indeed quantifiable. For example, suppose that I prefer apples to oranges; that is, I enjoy consuming apples more than oranges. Phrased differently, I think it would be fair to state that I like apples more than I like oranges. Thus, the issue that I have with the notion of quantifying feelings is not that the idea that our feelings are inherently incapable of being measured; but rather the idea that we can assign them some arbitrary numeric value.

There are numerous economic theories that I believe, when taken together, help lay a foundation for the articulation of a way in which we might very roughly quantify the magnitude of a person’s feelings. I explore them below, but please note that I provide only a highly simplified, basic explanation of each (which is, frankly, all I’m capable of). My explanations also generally assume that people will act according to their true feelings — that is, they won’t make decisions based on outside influences such as external pressure, i.e. from family, a partner, a difficult financial situation, and so forth. As always, numbers are not my forte, so please let me know of any mistakes I’ve made!

Revisiting the Economic Theory of Utility

There are two primary approaches with respect to the broader economic theory of utility, ordinal utility and cardinal utility. The concept of ordinal utility holds that the satisfaction a consumer derives from consumption of a good or service cannot be scaled in numbers, but can be arranged in the order of preference. Conversely, the concept of cardinal utility posits that the satisfaction a consumer derives from consumption of a good or service can be scaled in countable numbers.

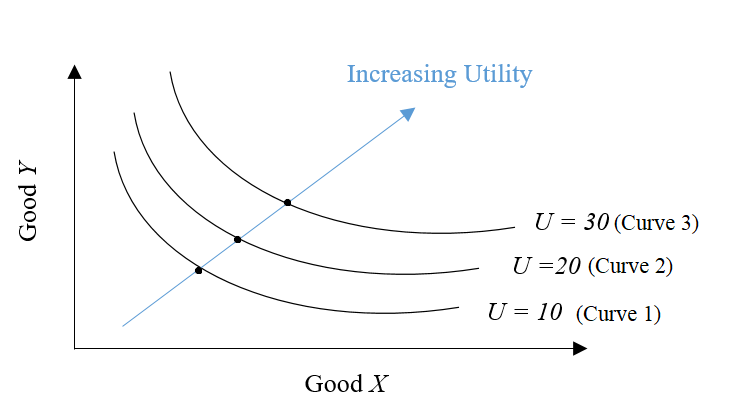

The graph below may help illustrate these conflicting approaches to utility theory. Each of the three lines on the graph is an indifference curve, which in turn represents various combinations of two goods (here, X and Y) that leave the consumer equally satisfied. For our very limited purposes, I like to think of these indifference curves as “states-of-being”: assume that the three curves below (labeled Curve \space 1, Curve \space 2, and Curve \space 3 respectively) each refer to a specific set of circumstances, or a particular “state-of-being” or “situation” (Situation \space 1, Situation \space 2, and Situation \space 3, if you will).

Conversely, ordinal utility theory suggests that the satisfaction a consumer derives from any particular situation is meaningful only in the context of how it compares to the others. Note that the utility levels (U=10, U=20 and U=30) so integral to the cardinal utility theory are void and meaningless here; under ordinal utility theory, the only substantive information we can gather about any one situation is how it measures up relative to another. For example, looking at the graph and disregarding the arbitrary utility levels, all we can really say about Situation \space 2 is that it makes the consumer happier than does Situation \space 1, and less happy than does Situation \space 3.

I find ordinal utility theory both more persuasive and more relevant in determining whether there is a realistic way to quantify our feelings. It sets the foundation for, and ties very well into, yet another economic theory that I think is even more salient with respect to exploring how we measure our feelings: the economic theory of revealed preferences .

Revealed Preferences

The economic theory of revealed preferences is one of my personal favorites, as I find it to be beautifully intuitive. First posited by Paul Samuelson, the theory of revealed preferences simply holds that a consumer’s purchasing behavior is the best indicator of their preferences — that is, that our behavior, actions, choices, and so forth, reveal our preferences. To that end, the theory of revealed preferences is very aptly named.

For example, suppose I am at a restaurant, choosing between fries and onion rings as a side dish; after some intense deliberation, I choose fries. Now, I can claim all I want that I love onion rings, but my choosing fries suggests otherwise. In that regard, I sometimes like to think that the theory of revealed preferences is well-captured by the old adage that “actions speak louder than words.” (There is a slight nuance to the theory of revealed preferences, in that income and prices must be held constant across different circumstances. Returning to the example above, it may well be that I do love onion rings — but perhaps not enough to pay, say, a $50 premium for them over fries, and certainly not after being laid off from my job and suffering a drastic reduction to my income.)

To that end, I am of the mind that we can measure — in a very rudimentary way — how much or how little a person loves one thing relative to how much they love other things, based on their behavior, choices, and decisions.

An Illustration: The Adventures of O, A, and B

A very basic hypothetical using three people, Person O, Person A, and Person B (remember them?), may help illustrate how the theory of revealed preferences can speak to how we measure our feelings. Suppose that Person O has the option to date either Person A or Person B, and ultimately chooses to date Person A. The theory of revealed preferences would interpret this decision as indicating that Person O prefers Person A to Person B; and for our purposes, we would in turn deduce that Person O loves or likes Person A more than she does Person B (if only real life were so simple!).

Recall that we are assuming that people act according to their true feelings — but of course, in reality people (and situations) are complicated, and rarely if ever are we perfectly rational actors. Person O may have chosen to date Person A because he or she was the “safe” option, or was more popular with O’s family — when in reality, Person O loves Person B more. Who knows?

But perhaps then, owing to this greater, suppressed love for Person B, Person O is never fully able to excise Person B from her life, and continues to communicate with Person B to the chagrin and ire of Person A. In such a case, I would contend that through this disregard of Person A’s feelings, Person O has revealed her true feelings — that is, her preference and apparently greater love for Person B — despite having ostensibly chosen Person A.

Or maybe not — maybe Person O chooses to date Person A, despite loving Person B more, but treats Person A with nothing but perfect respect, courtesy, and affection; and no one is ever the wiser about her true feelings. It is impossible to read into why people make the decisions that they do, or why they behave in the ways that they do; and so for the very limited purposes of our analysis, we will continue to assume that people act in accordance with how they truly feel — if I love Person A, I’ll date Person A, even if doing so is an unpopular move within my family.

Love in a Vacuum

I do believe then, that to a very limited extent, love can be quantified. “Quantified” may not be the best word — rather, we can draw conclusions about how much or how little a person loves something, relative to other things, based on their behavior, choices, and actions. What we cannot do is, in discrete numeric terms, quantify how much a person loves something in a vacuum.

This harkens back to the concept of ordinal utility, which suggests that we can measure the happiness that we derive from a certain situation, but only as it compares to the happiness we derive from other situations. We cannot conduct meaningful analysis about how much or how little we love something without any context or metric for comparison. In a vacuum, there is no persuasive way to accurately describe the magnitude of our feelings.

In my opinion, the act of “quantifying” love is a lot like that of trying to see the wind. We can’t see the wind in it of itself, just as we can’t numerically measure love in it of itself. But we can see the very tangible effects of the wind, and so measure its strength, perhaps by the objects it blows over. In a similar way, we may not be able to quantify the magnitude of human feeling, but we can derive some idea of its intensity based on its tangible effects — how it compels us to act, and what it compels us to do, in the face of viable alternatives.

The content of this post constitutes an expression purely of my personal opinion and conjecture, and accordingly, is intended only to entertain rather than to inform or instruct. If you see any errors, please *****@*******ol.me”>let me know.

mutandine usate

March 30, 2025 at 8:33 amI could not resist commenting. Perfectly written!

ciondolo pandora cuore personalizzato

August 23, 2025 at 3:01 pmYour point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

binance

August 23, 2025 at 11:07 pmReading your article helped me a lot and I agree with you. But I still have some doubts, can you clarify for me? I’ll keep an eye out for your answers.

orgone pietra

August 24, 2025 at 2:16 pmIntroducing to you the most prestigious online entertainment address today. Visit now to experience now!

regalo uomo 40 anni tecnologico

August 24, 2025 at 3:58 pmYour point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

regalo uomo 60 anni amico

August 25, 2025 at 3:51 pmI do consider all the ideas you’ve offered for your post. They’re really convincing and will definitely work. Still, the posts are very brief for beginners. May you please lengthen them a little from next time? Thank you for the post.

orgone ciondolo

August 25, 2025 at 5:18 pmI would like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this website. I am hoping to see the same high-grade blog posts by you in the future as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get my own, personal blog now 😉

ciondolo girasole pandora prezzo

August 26, 2025 at 3:04 amWrite more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You clearly know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence on just posting videos to your weblog when you could be giving us something informative to read?

idee regalo ragazza di 20 anni

August 26, 2025 at 12:32 pmef59e6

zoritoler imol

September 3, 2025 at 9:21 amThis is the proper blog for anybody who needs to seek out out about this topic. You understand so much its almost exhausting to argue with you (not that I really would need…HaHa). You undoubtedly put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just nice!

orgone pyramids meaning

September 5, 2025 at 3:01 pmThis is very interesting, You’re a very professional blogger.I have joined your rss feed and stay up for in the hunt for extra ofyour fantastic post. Also, I have shared your web sitein my social networks

binance

September 10, 2025 at 8:47 pmCan you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

creación de cuenta en Binance

September 28, 2025 at 8:58 pmThank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Anonymous

October 9, 2025 at 12:37 pmYour point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

binance

October 27, 2025 at 7:16 pmYour article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

binance Konta Izveidosana

November 18, 2025 at 6:00 amThank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

binance register

December 16, 2025 at 8:07 pmThank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

hepatoburn

December 26, 2025 at 12:03 pm**hepatoburn**

hepatoburn is a high-quality, plant-forward dietary blend created to nourish liver function, encourage a healthy metabolic rhythm, and support the bodys natural fat-processing pathways.

biodentex

January 23, 2026 at 12:05 am**biodentex**

biodentex is an advanced oral wellness supplement made for anyone who wants firmer-feeling teeth, calmer gums, and naturally cleaner breath over timewithout relying solely on toothpaste, mouthwash, or strong chemical rinses.

neurosharp

January 29, 2026 at 5:38 pm**neurosharp**

Neuro Sharp is an advanced cognitive support formula designed to help you stay mentally sharp, focused, and confident throughout your day.

backbiome

January 30, 2026 at 3:18 am**backbiome**

Mitolyn is a carefully developed, plant-based formula created to help support metabolic efficiency and encourage healthy, lasting weight management.

QQ88

January 30, 2026 at 2:23 pmQQ88 LÀ NHÀ CÁI CƯỢC UY TÍN SỐ 1 VN

av 女優

January 31, 2026 at 2:07 amI’ve been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or weblog posts on this kind of

area . Exploring in Yahoo I ultimately stumbled upon this website.

Studying this info So i’m glad to convey that I have a very excellent uncanny feeling I

came upon just what I needed. I such a lot without a doubt will make certain to do not forget this web site and give

it a look on a constant basis.

av 在线

February 1, 2026 at 10:24 pmHi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

binance

February 2, 2026 at 12:02 amThank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

QQ88

February 2, 2026 at 7:20 amQQ88 mang đến nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến được tối ưu hiệu suất, giúp người dùng truy cập nhanh, thao tác mượt và trải nghiệm ổn định.

1win affiliate program

February 2, 2026 at 3:03 pmGreat article! That is the kind of info that are meant

to be shared around the net. Shame on Google for no longer

positioning this submit higher! Come on over and visit my website .

Thank you =)